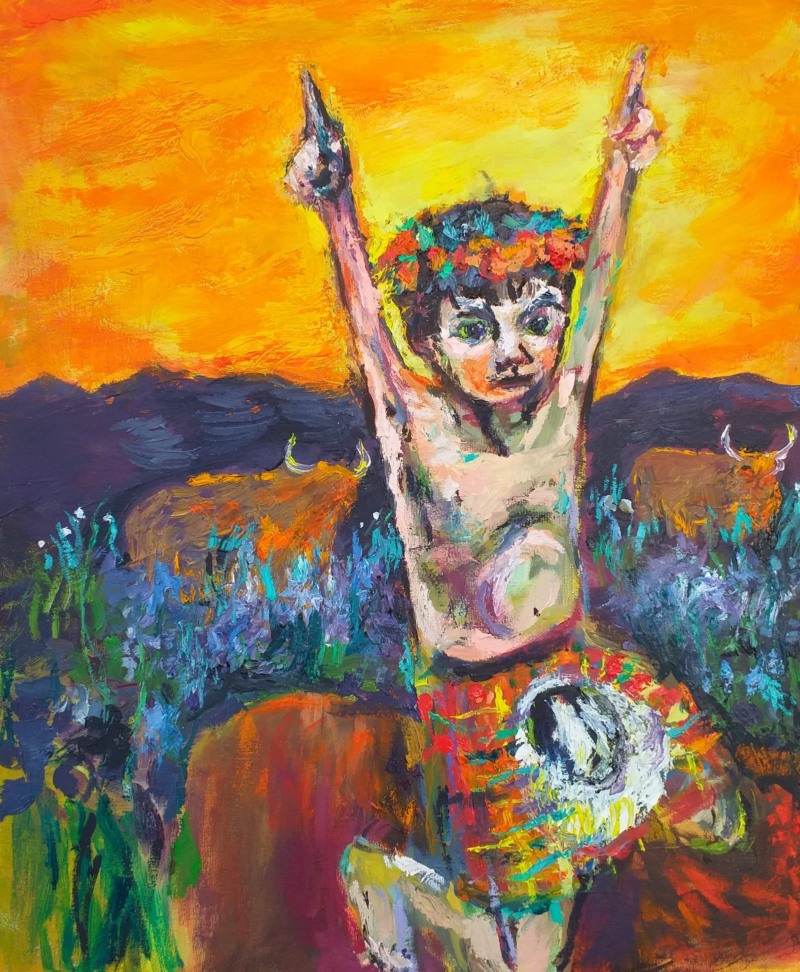

J M Fulton is an award-winning Scottish artist whose paintings are full of bold colour and expression. He trained at Glasgow School of Art and is inspired by the heritage of modern Scottish painting.

He believes in expressing ‘Scottishness’ in painting as part of the tradition of European Expressionism.

He has previously been awarded a scholarship to study in Florence from the Royal Scottish Academy and lives and works in the East End of Glasgow.

As an artist he has worked for years bringing the joy of art to hard-to-reach groups in social care, and with children as well as adults with learning disabilities.

His new work reflects his loves of European Expressionism and children. He has two children of his own, aged 2 and 4.

What is your art about?

My paintings come under the title ‘Children of Scotland’. They are expressive paintings of children in Scotland that combine my loves of Scottish culture, kids (I have two wee ones) and European Expressionist painting.

My driving force is the humanity that art can make us feel. What people feel when they see the children in my paintings and my own humanity expressed when I paint them with as much feeling as I can.

The children in my pictures are imaginary and they exist in an invented Scotland. I owe lots to a feeling of Scottishness and I am fascinated by the idea of a uniquely Scottish tradition in painting.

Why are your paintings Scottish?

I am a Scot and bringing identifiable Scottish objects into my work just seems to happen – I suppose it must be a big part of my identity and part of what I want to say with paint.

Our landscape in Scotland obviously gorgeous but what is more beautiful for me is the humanity, the kindness and openness, of the people who live here. I think that’s why I paint Scottish children.

What inspires you?

I’m inspired by all the artists I love. If I see a reproduction of a Van Gogh it just seems obvious that we need to try and keep doing something like that because we still find it so beautiful.

In today’s world of smart phones, fleeting images and throwaway culture it just seems important to try to get something direct, from inside a human spirit, expressed out. The urge to paint is older than anything we can touch – I’m just following my human nature.

Why do you paint children?

I started painting children as soon as I became a father but I’ve always loved paintings with children in them, especially those of Joan Eardley who painted weans living in post-war Glasgow.

When you see a child in a painting you can sympathise and relate to them in a direct way. There’s none of the politics (of power and sex) that you get with adults. They can just exist in the world of the painting.

I’ve always had really deep feelings for the paintings of Joan Eardley who painted children living just down the road from where I live, in the Townhead area of Glasgow, in the 1950s. They’ve brought out the most emotion I’ve ever felt from a painting.

What is your painting process?

I start my paintings with nothing, no model or photograph, because I’ve found that for me this is the only way I feel totally free – as an artist working on instinct. I’m thrilled by the idea that the first humans painted beautiful, tender pictures on the walls of caves before they had language. I still believe we have that natural ability in us in the same way we do singing or dance: to bring what we feel inside of us out.

When I was at GSA there was still a big emphasis on life drawing and students would spend weeks at a time in the life room. So all that knowledge of drawing and painting figures is in me.

One tutor there was major contemporary figurative painter Moyna Flannigan. She advocated for “instinctive painting” – just trusting your natural ability rather than using any references. And only now I feel that is what works for me.

No models or photographs?

I’ve read that Monet said he was most interested in what existed between him and the canvas rather than any particular subject. I also read Jackson Pollock saying he didn’t need to paint from nature because he was nature.

There is an excited, heightened state that artists get when doing a painting. Maybe it is inspiration. My process is really about focusing on that and following what it tells me. Sometimes I will start a painting with an idea of a composition (I sketch loads from imagination) or maybe something I want to try with colour. But when the painting begins it is really just about following my feeling – maybe quite a prehistoric thing to do.

"There is an excited, heightened state that artists get when doing a painting."

I’m excited by colour and colourists like Van Gogh who risk everything on the canvas while the painting is ‘live’. So often I will try to heighten the colour or place contrasting colours beside or on top of each other to see what effect they can create for the eye. Basically, I’m trying to get the painting to be alive – as a alive as possible – through playing with the force of colour.

Also, I like the brushstrokes to come when I’m in a more excited, agitated state. I think that’s where a lot of a painter’s humanity can be expressed from.

And the Scottish tradition?

Even at high school, when I was first beginning to feel like I was an artist, I remember being most excited by painters from Scotland – Glasgow in fact. Painters like Gaugin, Van Gogh and Egon Scheiele were obviously mesmerising but the idea that people like Ken Currie and Peter Howson were creating profound work in Glasgow and that they were not from the past but actually alive and working. Well, that was a bolt of lightning!

I went to Glasgow School of Art straight from school and was delighted to be in what felt like the hub of this a painting tradition. I loved to think that artists like Joan Eardley, MacBryde and Colquhoun, Peter Howson and Ken Currie had all been there before me, struggling and forging what painting in Scotland could be. I also discovered the German Expressionists when I was there ( Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Beckman etc) and saw how they had shown their turbulent society in brightly coloured, raw paintings.

I remember writing a dissertation (I even remember interviewing then Head of Painting Alexander Moffat for it) where I was desperate to try to understand what a peculiarly Scottish tradition of painting could be. What were its defining characteristics? Where had it came from?

I think I concluded that a kind of northern European angst, maybe from living in cold dark country, was central. (Think of the early paintings of fishermen by John Bellany).

But also there was a celebration of colour, a joie de vivre shared with the other Gaels of France. (Think of the Scottish Colourists).

I suppose it’s hard to pin down, especially in today’s interconnected world, but it’s something felt anyway.